Agent Frameworks for the Rest of Us

A Mental Map

How do you build an AI agent? There are all these frameworks (LangChain/LangGraph, Vercel AI SDK, PydanticAI, Claude Agent SDK, Mastra, OpenCode) to help you build agents. What actually makes them different from one another? The present report shares my findings diving into Agent Frameworks.

Who is the “Rest of Us”? People that are not technical enough to just “get it”. I am a PM, somewhat technical but not overly so. And as such this report certainly contains inaccuracies or errors. Feedback will improve it :)

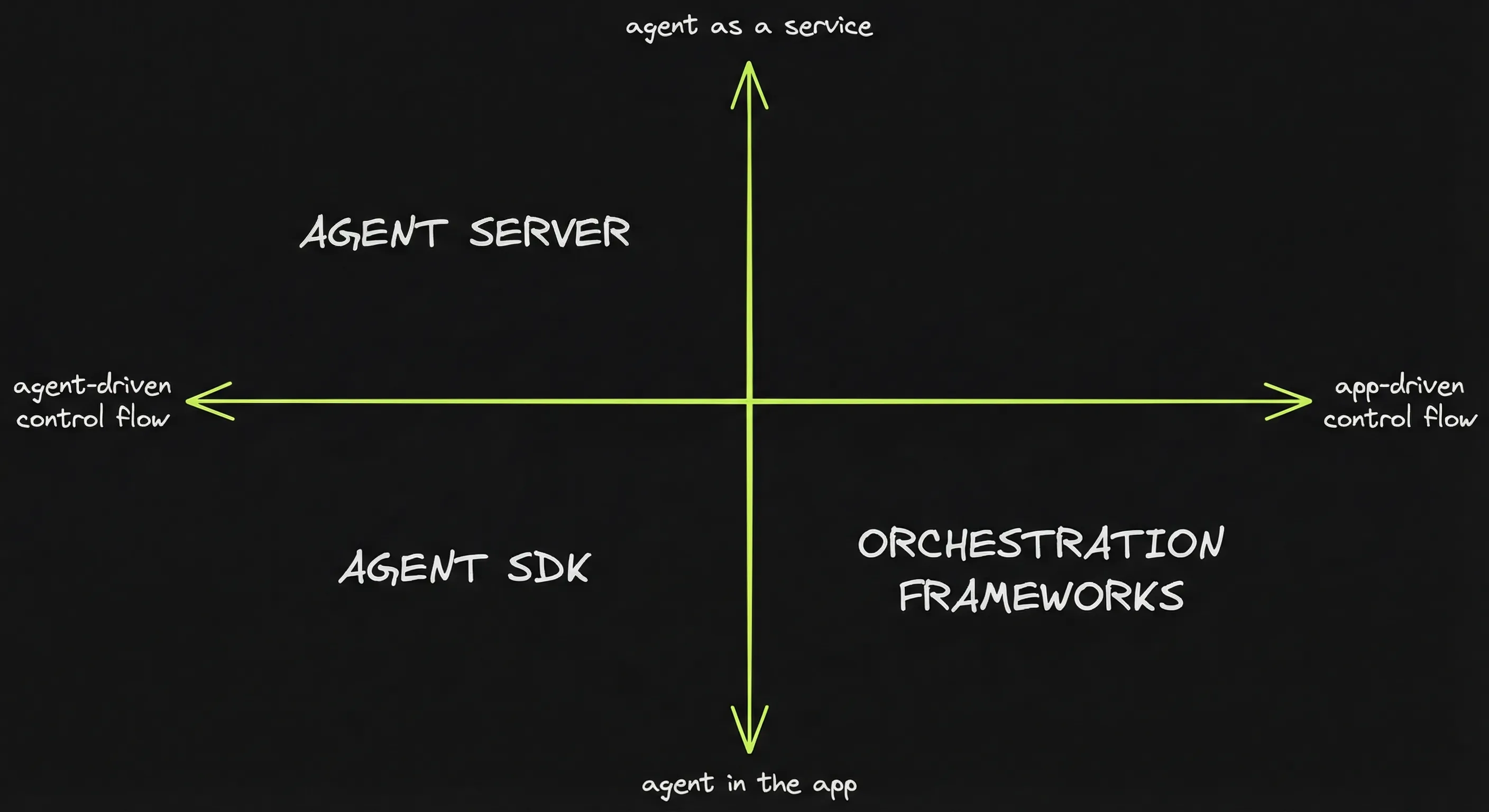

Mapping the frameworks: I need maps to orient myself. I’ve come to think of frameworks as belonging to one of the following 3 categories.

- Orchestration frameworks: LangGraph, PydanticAI, Mastra, Vercel AI SDK

- Agent SDKs: Claude Agent SDK, Pi SDK

- Agent servers: Opencode

More specifically, frameworks are positioned based on 2 questions:

- Where does orchestration live?

Orchestration outside the agent loop (app-driven) ↔ orchestration inside the agent loop (agent-driven). - Where is the agent boundary?

Agent IN the app (agent-as-a-feature) ↔ agent IS the app (agent-as-a-service).

What you can expect in the following parts:

- Part 1: What “agent” means — the three ingredients every agent is made of.

- Part 2: How frameworks differ in who decides what happens next — your code or the model.

- Part 3: Why the most powerful agent tool is a Unix shell, and what that implies.

- Part 4: What it takes to turn an agent library into an agent server.

- Part 5: Real projects that made different architectural choices, and what you can learn from them.

Part 1 - What’s an agent, anyway?

An agent is an LLM running tools in a loop:

- Simon Willison’s one-liner — “An LLM agent runs tools in a loop to achieve a goal” — has become the closest thing to a consensus definition.

- Harrison Chase (LangChain) said the same thing differently: “The core algorithm is actually the same — it’s an LLM running in a loop calling tools.”

So an agent has 3 ingredients:

- An LLM

- Tools

- A loop.

Let’s unpack each one.

What an LLM does

An LLM is a text-completion machine. You send it a chain of characters. It predicts the next most probable character, then the next, until it stops.

When you ask a question, the sequence of most probable next characters is likely to be a sentence that resembles an answer to your question.

An LLM can only produce text. It cannot browse the web. It cannot run a calculation using a program. It cannot read a file or call an API.

What a tool is

A tool gives an LLM capabilities it does not have natively. Tools enable:

- Things LLM cannot do: access the internet, query a database, execute code.

- Things LLM do badly: arithmetic, find exact-matches in a document…

The LLM cannot execute tools on its own though:

- The LLM returns a structured object specifying which tool to call.

- The host program runs the tool.

- The host program passes the result back to the LLM.

How LLMs learned to call tools

We said that an LLM can only produce text. So how does it ask for calling a tool? Does it return a text saying “I need to run the calculator” or something like that?

To call a tool, the LLM returns a JSON object that says which tool it wants to run, and with which parameters.

For example, if the LLM wants to check the weather in Paris, instead of responding with text, it returns something like:

{

"type": "tool_use",

"name": "get_weather",

"input": { "city": "Paris" }

}But how did the LLM learn to generate such JSON objects as the most likely chain of characters in the middle of a conversation in plain English?

The original training data contains no tool-calling examples. Nobody writes “output a JSON object to invoke a calculator function” on the internet.

LLMs are specifically trained to learn when to use tools through fine-tuning on tool-use transcripts:

- The models are trained on many examples of conversations where the assistant produces structured function invocations, receives results, and continues. OpenAI shipped this first commercially (June 2023, GPT-3.5/GPT-4), and other providers followed.

- The model does not learn each specific tool. It learns the general pattern: when to invoke, how to format the call, how to integrate the result.

- The specific tools available are described in the prompt — the model reads their names, descriptions, and parameter schemas as text.

Tool hallucination is a consequence of tool training. The model can generate calls to tools that were never provided, or fabricate parameters. UC Berkeley’s Gorilla project (Berkeley Function-Calling Leaderboard) has documented this systematically — it is one reason agent frameworks invest in validation and error handling.

The two-step pattern

When you call an LLM with tools enabled, two things can happen:

- The model responds with text — it has enough information to answer directly.

- The model responds with a tool-call request — a structured object specifying which tool to call and what arguments to pass.

If the model requests a tool call, your code executes it. You send the result back as a follow-up message. The model uses that result to formulate its answer — or to request yet another tool call.

Tool use always involves at least two model calls.:

- The first model call returns a tool call request

- The second model call is provided the conversation + the result of the tool call.

messages = [system_prompt, user_message]

# LLM Call 1 — send the conversation + list of available tools

response = llm(messages, tools=available_tools)

# Did the model respond with text, or with a tool-call request?

if response.has_tool_call:

tool_call = response.tool_call

result = execute(tool_call.name, tool_call.arguments)

messages.append(tool_call)

messages.append(tool_result(tool_call.id, result))

# LLM Call 2 — send the conversation again, now including the tool result

response = llm(messages, tools=available_tools)

The agentic loop

Many tasks require more than one tool call. A coding assistant might read a file, edit it, run the tests, check output, fix a failing test — all in sequence. The model cannot know in advance how many steps it will need.

The solution: wrap the two-step pattern in a loop.

messages = [system_prompt, user_message]

loop:

response = llm(messages, tools=available_tools)

if response.has_tool_calls:

for call in response.tool_calls:

result = execute(call.name, call.arguments)

messages.append(call)

messages.append(tool_result(call.id, result))

continue

break # no tool calls — done

print(response.text)The model loops: calling tools, receiving results, deciding what to do next, until it produces text instead of another tool call.

In practice, you add guardrails: a maximum number of iterations, a cost budget, validation checks. But the core mechanism is the same.

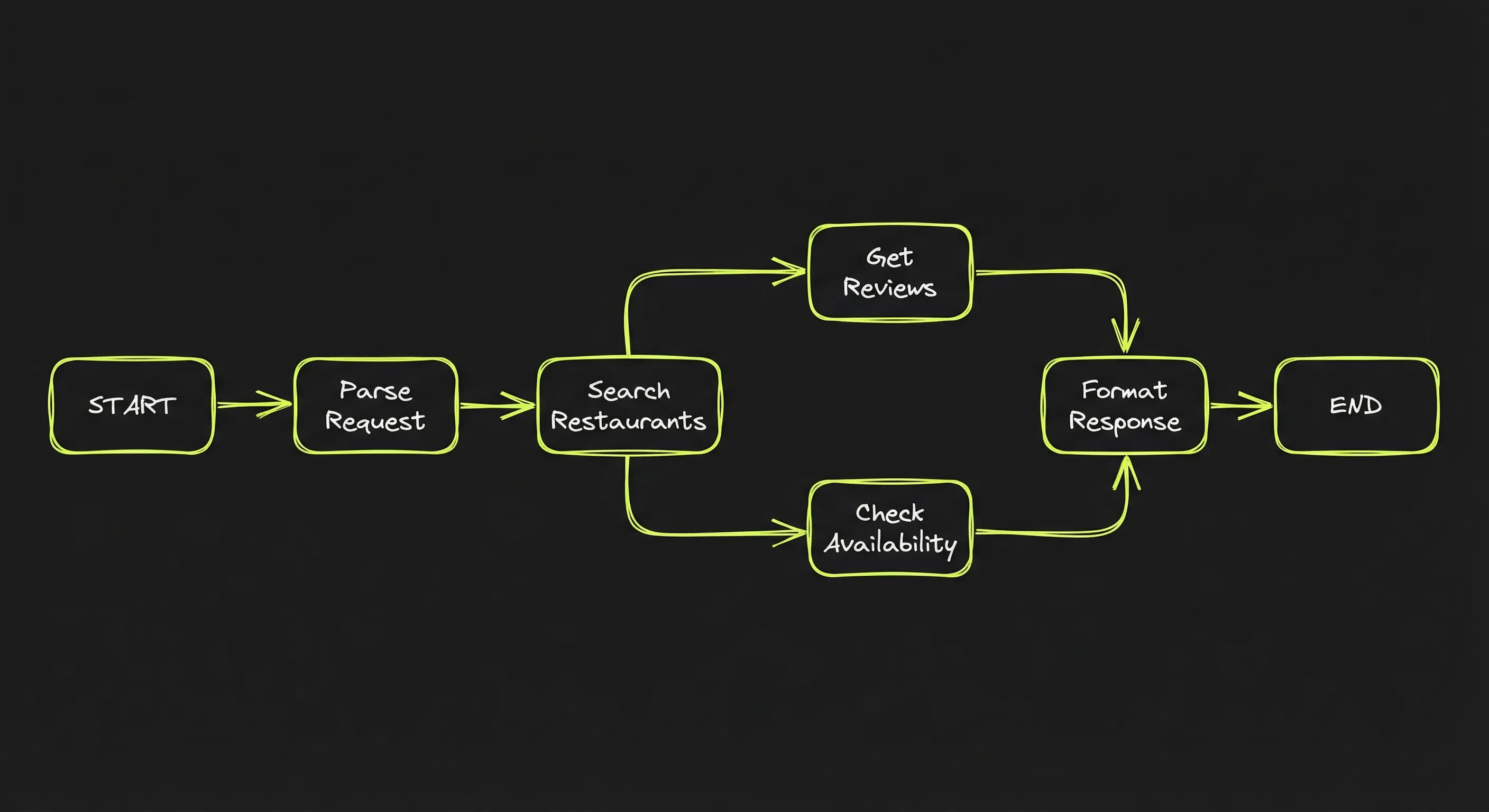

What this looks like in practice. Here is a simplified trace of an agent booking a restaurant. Each block is one iteration of the loop:

User: "Find me a good Italian restaurant near the office

for Friday dinner, 4 people."

Agent: [tool: search_web("Italian restaurants near 123 Main St")]

→ 3 results: Trattoria Roma, Pasta House, Il Giardino

Agent: [tool: get_reviews("Trattoria Roma", "Pasta House", "Il Giardino")]

→ Trattoria Roma: 4.7★, Pasta House: 3.9★, Il Giardino: 4.5★

Agent: [tool: check_availability("Trattoria Roma", friday, party=4)]

→ available at 7:30 PM and 8:00 PM

Agent: "Trattoria Roma is the best rated (4.7★) and has two

slots Friday for 4: 7:30 PM or 8:00 PM.

Want me to book one?"Four loop iterations. Three tool calls, then a text response that ends the loop. The agent decided which restaurants to look up, which one to check availability for first (the highest rated), and when it had enough information to stop. The program just ran the tools and passed results back.

What to keep in mind

- An agent is an LLM + tools + a loop. Every agent framework — PydanticAI, LangGraph, Claude Agent SDK, OpenAI Agents SDK — implements some version of this loop. They differ in what they build around it.

- Tool calling is a two-step pattern. The model requests, your code executes, the result feeds back.

- The model decides when to stop. In the simplest case, it stops when it produces text instead of a tool call. But in real systems, stop conditions can be implemented based on budgets, validation, user acceptance, timeouts.

Part 2 - Where orchestration lives

Frameworks differ on who owns the orchestration: the app (orchestration frameworks) or the agent (agent sdks)?

From prompting to agents

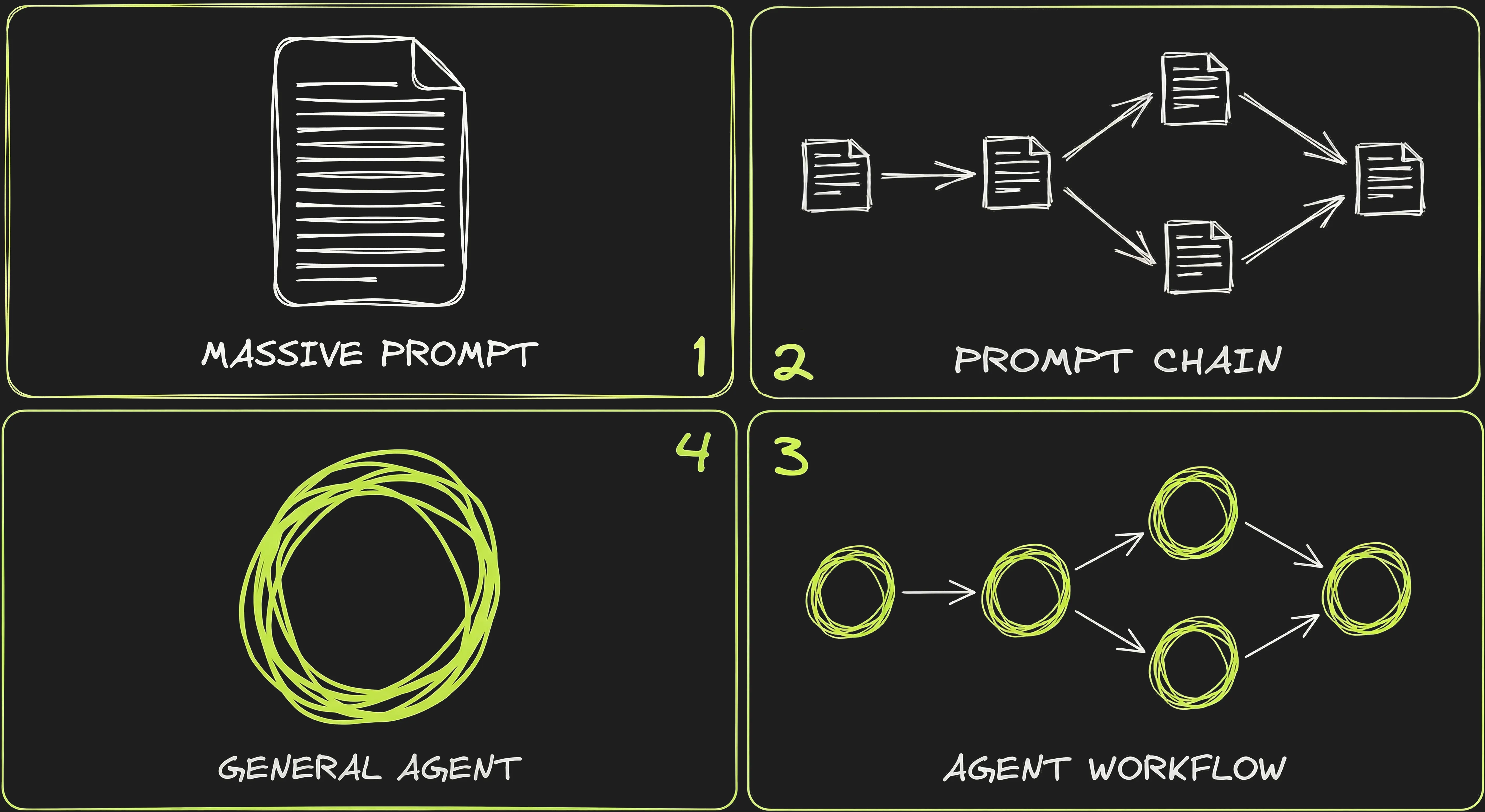

1️⃣ The Massive Prompt

At first people would cram all the instructions, context, examples, and output format into a single call and hope the LLM would get it right in one pass.

This was brittle:

- LLMs were unreliable on tasks that require multiple steps or intermediate reasoning.

- Long prompts produced less predictable output: some parts of the prompt would get overlooked or confuse the model. The longer the prompt, the less consistent the results over multiple runs.

- Long prompts were easy to break: even small changes could alter dramatically the behaviour.

2️⃣ The Prompt Chain

Getting better results meant breaking things down. Instead of one monolithic prompt, you split the task into smaller steps — each with its own prompt, its own expected output, and its own validation logic. The output of step 1 feeds into step 2, and so on.

With prompt chaining each step has a narrow, well-defined responsibility.

3️⃣ The Workflow

Once you add tool calling, each step in the chain can now do real work — query a database, search the web, validate data against an API. The chain becomes a workflow: a sequence of steps implementing the agentic loop, connected by routing logic.

4️⃣ The “General Agent”

With better models, another option emerged: instead of defining the workflow step by step, give the agent tools and a goal, and let it figure out the steps on its own.

We are somewhat back to 1️⃣ — one prompt, one call — but with the addition of tool calling and much better (thinking) models. This is agent-driven control flow, and it coexists with workflows rather than replacing them.

An “orchestration” definition

Whether you define the workflow yourself (steps 2️⃣ and 3️⃣) or let the agent figure it out (step 4️⃣), someone has to decide the structure — the sequence of actions that leads to the outcome. That’s what orchestration means.

Orchestration is the logic that structures the flow: the sequence of steps, the transitions between them, and how the next step is determined.

This section focuses on the question: who owns that logic? who owns the control flow?

- App-driven control flow: the logic is decided by the developer and “physically constrained” through code.

- Agent-driven control flow: the logic is suggested by the developer and it is left to the LLM / agent to follow the instructions.

App-driven control flow

Within the app-driven control flow, the app owns the state machine:

- The developer defines the graph: the nodes (steps), the edges (transitions), the routing logic.

- The LLM is a component called within each step but the app enforces the flow defined by the developer.

Anthropic’s “Building Effective Agents” blog post catalogs several variants of app-driven control flow:

- Prompt chaining — each LLM call processes the output of the previous one.

- Routing — an LLM classifies an input and directs it to a specialized follow-up.

- Parallelization — LLMs work simultaneously on subtasks, outputs are aggregated.

- Orchestrator-workers — a central LLM breaks down tasks and delegates to workers.

- Evaluator-optimizer — one LLM generates, another evaluates, in a loop.

Orchestration frameworks provide the infrastructure for building these workflows. They abstract the plumbing so that developers can focus on the workflow logic. More specifically they handle:

- Parsing tool calls, feeding results back into the next model call.

- Stop conditions, error handling, retries, timeouts.

Here is schematically how the developer would implement the restaurant reservation workflow:

workflow = new Workflow()

workflow.add_step("search", search_restaurants)

workflow.add_step("get_reviews", fetch_reviews)

workflow.add_step("check_avail", check_availability)

workflow.add_step("respond", format_response)

workflow.add_route("search" → "get_reviews")

workflow.add_route("get_reviews" → "check_avail")

workflow.add_route("check_avail" → "respond")

result = workflow.run("Italian restaurant near the office, Friday, 4 people")On top of that, the developer defines the functions for each step. For example, search_restaurants might use the LLM internally to parse search results:

function search_restaurants(query, location):

raw_results = web_search(query + " near " + location)

parsed = llm("Extract restaurant names and addresses from: " + raw_results)

return parsedHow the main orchestration frameworks compare:

- LangGraph (Python + TypeScript) was the first such framework. You wire every node and edge by hand.

- PydanticAI (Python) takes a different approach: graph transitions are defined as return type annotations on nodes, so the type checker enforces valid transitions at write-time.

- Vercel AI SDK (Typescript) started as a low-level tool loop + unified provider layer, then added agent abstractions in v5-v6 (2025).

- Mastra (Typescript) builds on top of Vercel AI SDK — it delegates model routing and tool calling to the AI SDK and adds the application layer on top (workflows, memory, evaluation).

There are other such orchestration frameworks. Cues to recognize app-driven control flows:

- Explicit stage transitions in code or config.

- Multiple different prompts or schemas.

- The app decides when to request user input.

- The model may call tools within a step, but the macro progression is app-owned.

Agent-driven control flow

With Agent-driven control flow, the agent decides what happens next.

It looks like this:

agent = Agent(

model = "claude-sonnet",

system_prompt = "You are a coding assistant. Read files, edit code,

run tests.",

tools = [read_file, edit_file, run_tests, search_codebase],

max_turns = 50

)

result = agent.run("Fix the failing test in src/auth.ts")The agent decides:

- What to read first.

- What to edit.

- When to run tests.

- Whether to try a different approach after a failure.

- When to stop.

The orchestration moves inside the agent loop: it’s not enforced by the app but left to the model’s own judgment. Agent SDKs provide a “harness” that can be customized by the developer. This harness provide orchestration cues to the model to steer it towards the expected goals:

- System prompts, policies and instructions (in agent.md or similar): the rules of the road: what to do, what not to do, how to behave.

- Tools: what pre-packaged tools are available to search, fetch, edit, run commands, apply patches.

- Permissions: which tools are allowed, under what conditions, with what scoping.

- Skills: pre-packaged behaviours and assets the agent can invoke.

- Hooks / callbacks: places the host can intercept or augment behavior (logging, approvals, guardrails).

This report examines three agent SDKs that implement agent-driven control flow:

- Claude Agent SDK exposes the Claude Code engine as a library, with all the harness elements above built in.

- Pi SDK is an opinionated, minimalistic framework. Notably it can work in environments without bash or filesystem access, relying on structured tool calls instead.

- OpenCode ships as a server with an HTTP API — the harness plus a ready-made service boundary.

There are other agent-driven frameworks. Typical signs of agent-driven control flow:

- The hosting app is thin: it relays messages, enforces permissions, renders results.

- The logic lives in the harness in the form of system prompts, context files, skills and other “capabilities” that steer the agent towards the expected outcome.

What to keep in mind

Three points from this section:

- Orchestration is about who decides what happens next. In app-driven control flow, the developer defines the graph. In agent-driven control flow, the model decides based on goals, tools, and prompts. Both are valid — the choice depends on how predictable the task is.

- Orchestration frameworks handle the plumbing. Whether you choose app-driven or agent-driven, frameworks give you the loop, tool wiring, and error handling so you can focus on the logic — not on parsing JSON and managing retries.

- In agent-driven systems, the harness replaces the graph. The agent has more freedom, but it is not unsupervised. System prompts, permissions, skills, and hooks are what steer it. The harness is the developer’s control surface when there is no explicit workflow.

- Orchestration libraries are adding agent-driven control flow: LangChain Deep Agents and PydanticAI both list deep agents as a first-class pattern.

Part 3 - Two tools to rule them all

The tools provided to an agent encode assumptions about how things should be done. A search_web → get_reviews → check_availability pipeline implies a specific strategy. It limits the ability of the model to figure out how to reach the goal.

Bash and the file system in contrast are universal tools that Agent SDKs have made a choice to consider a given. In this part, I’ll look into why and how those tools change the game.

The limits of predefined tools

Tools define what the agent can do. If you give it search_web, read_file, and send_email, those are its capabilities. Nothing more.

Every capability must be anticipated and implemented in advance:

- Want the agent to compress a file? You need a

compress_filetool. - Want it to resize an image? You need a

resize_imagetool. - Want it to check disk space, parse a CSV, or ping a server? Each one requires a tool.

Even slight changes in the task require updating the tool set. Say you built a send_email(to, subject, body) tool. Now the user wants to attach a file — you need an attachments parameter. Then they want to CC someone — another parameter. Each small requirement change means updating the tool’s schema and implementation.

Designing an effective tool list is a hard balance to strike. Anthropic’s guidance on tool design puts it directly: “Too many tools or overlapping tools can distract agents from pursuing efficient strategies.” But too few tools, or tools that are too narrow, can prevent the agent from solving the problem at all.

Bash as the universal tool

Bash is the Unix shell: a command-line interface that has been around since 1989

It is the standard way to interact with Unix-like systems (Linux, macOS). You type commands, the shell executes them, you see the output.

Consider a task like: “find all log files from this week, check which ones contain errors, and count the number of errors in each.”

- With predefined tools, you would need

list_fileswith date filtering,search_fileto find matches,count_matchesper file — three separate tools, plus the logic to combine the results. - With bash: 3 commands. No tool definitions, no schema changes if the task evolves.

# Find log files from the last 7 days

find . -name "*.log" -mtime -7

# Which ones contain errors

grep -l "ERROR" $(find . -name "*.log" -mtime -7)

# Count errors in each

for f in $(find . -name "*.log" -mtime -7); do

echo "$f: $(grep -c 'ERROR' "$f") errors"

doneWhy does bash matter for agents?

Bash scripts can replace specialized tools:

- Giving an agent bash access is giving it access to the entire Unix environment: file operations, network requests, text processing, program execution

- And the ability to combine them in ways you did not anticipate.

Vercel achieved 100% success rate. 3.5x faster. 37% fewer tokens :

- Their text-to-SQL agent d0 had 17 specialized tools (query builders, schema inspectors, result formatters) and achieved an 80% success rate.

- Then they “deleted most of it and stripped the agent down to a single tool: execute arbitrary bash commands.”

- The result: one general-purpose tool outperformed seventeen specialized ones.

Bash is not just more flexible — it is also faster.

Each tool call means an additional inference. Calling a lot of tools is expensive:

- Remember the two-step pattern: the model requests a tool call, the system executes it, the result feeds back.

- For a task requiring 10 tool calls, that is 10 inference passes.

With bash, the agent can write a script that chains multiple operations together and save on intermediate inferences:

- The CodeAct research paper (ICML 2024) found code-based actions achieved up to 20% higher success rates than JSON-based tool calls.

- Manus adopted a similar approach from their launch using fewer than 20 atomic functions, and offload the real work to generated scripts running inside a sandbox.

- Anthropic and Cloudflare’s Code Mode experiment confirmed that writing code beats tool calling

The filesystem as the universal persistence layer

To persist an information, a user-facing artifact, a plan or intermediate results, an agent needs a tool and a storage mechanism.

Predefined persistence tools have the same problem as predefined action tools:

- A

save_note(title, content)tool works for text notes. But what about images? JSON structures? Binary files? A directory of related files? - The tool’s schema defines and limits what can be stored. Each storage mechanism has its own interface, its own constraints.

The filesystem has no predefined schema or constraints:

- A file can contain anything: Markdown, JSON, images, binaries, code. A directory can organize files however makes sense.

- The agent decides where to put it, what to write, what to name it, how to structure it.

The filesystem allows the agent to communicate with itself:

- The agent can store information that it may need further down the road. Manus describes this as “File System as Extended Memory”: “unlimited in size, persistent by nature, and directly operable by the agent itself.”

- The filesystem also allows the agent to share memories between sessions, removing the need for elaborate memorization / retrieval tools.

What to keep in mind

- Bash is a universal tool. Instead of anticipating every capability and implementing a specific tool, you give the agent access to the Unix environment. It can compose arbitrary operations from basic primitives — and LLMs are already trained on how to do this.

- The filesystem is universal persistence. Instead of defining schemas for what the agent can store, you give it a directory. It can write any file type, organize however makes sense, and the files persist across sessions for free.

- All major agent SDKs assume both. The Claude Agent SDK, OpenCode, and Codex all ship bash and filesystem tools as built-in. Pi SDK is a notable exception — it can work without filesystem access.

- This has architectural consequences. Bash and filesystem access require a runtime that provides them.

- An alternative is emerging: reimplement the interpreter. Vercel’s

just-bashis a bash interpreter written in TypeScript: 75+ Unix commands reimplemented with a virtual in-memory filesystem. No real shell, no real filesystem, no container needed. Pydantic’smontydoes the same for Python: a subset interpreter written in Rust, whereopen(),subprocess, andexec()simply do not exist.

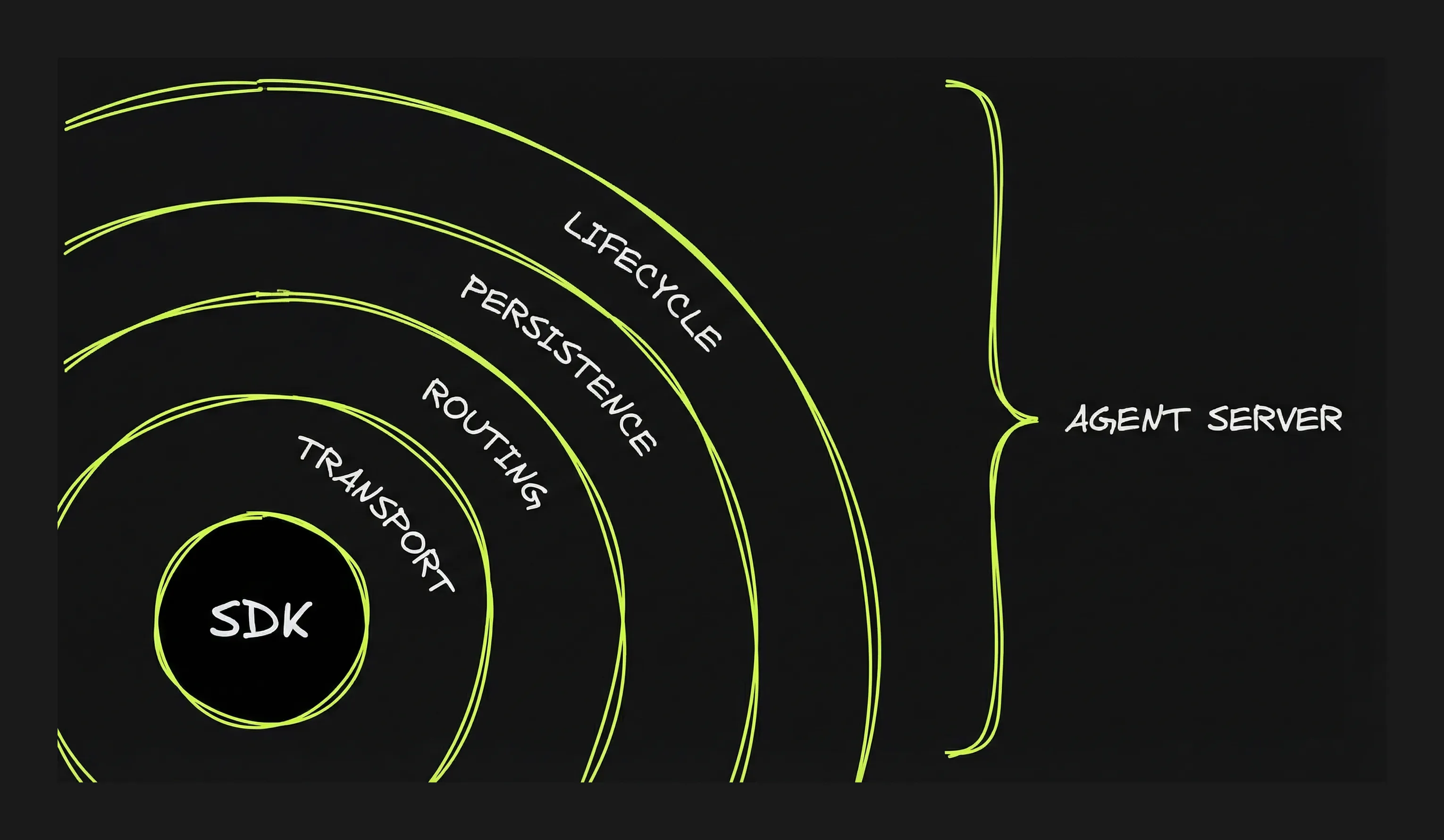

Part 4 - Agent SDK to Agent Server: crossing the service boundary

An agent can be many thing: ephemeral or long-lived, stateful or stateless, automating processes behind-the-scene or user-facing.

How do these behavioural features map with technical capabilities provided by the agent frameworks? And the other way around, OpenCode has a server-client architecture while other frameworks are libraries: how does that matter when you want to build an agent

In this part, I’m looking at how agent behaviours and agent implementation details are related. In particular what technical layers need to be implemented to go from an Agent SDK to an Agent Server (OpenCode).

What’s an Agent “SDK” anyway?

Libraries and services

Think of the difference between Excel and Google Sheets.

An Excel spreadsheet lives on your machine. Nobody else can see it while you’re working. It exists on your machine and only your machine.

Google Sheets lives on Google’s servers. You open it in a browser, but the spreadsheet is not on your machine. You can close your browser and it’s still there. You can open it from your phone, from another laptop. It keeps running whether or not you’re connected.

Excel behaves in this example like a library, it’s embedded. Google Sheets is “hosted”: it lives behind the service boundary. It’s a service.

The lifecycle of a service is not bound to the lifecycle of the client that is calling it. The service boundary is not just about separate physical machines — it is about whether a capability runs inside an application or as a separate, independent process. An application calls a library directly; it connects to a service over a protocol.

A more technical example: databases.

SQLite is embedded. Your application links the library, calls functions directly. No service boundary. When your app exits, SQLite exits.

PostgreSQL is hosted. It runs as a separate server process. Your application connects over a socket, sends SQL as messages, receives results. Service boundary. PostgreSQL keeps running after your app disconnects.

What is the difference between an Agent SDK and a regular coding agent?

What’s the difference between Claude Agent SDK and Claude Code, between Codex SDK and Codex, between Pi coding agent and Pi SDK?

An Agent SDK provides the same kind of capabilities you would expect from a coding agent — but as a “programmable interface” (API) instead of a user interface

- Send a prompt, get a response — the equivalent of typing a message in Claude Code. In the SDK:

query(prompt). - Resume a previous conversation — pick up where you left off, with full context. In the SDK: pass a

sessionId. - Control which tools the agent can use — restrict it to read-only, or give it full access. In the SDK:

allowedTools. - Intercept the agent’s behavior — get notified before or after a tool call, log actions, add approval gates. In the SDK: hooks.

# Send a prompt to the Claude Agent SDK with a list of allowed tools

from claude_agent_sdk import query

async for message in query(

prompt="Run the test suite and fix any failures",

options={"allowed_tools": ["Bash", "Read", "Edit"]}

):

print(message)With an Agent SDK, you may:

- Automate tasks

- Extend an existing app with agentic features

Example: automated code review in CI.

- You run the Claude Agent SDK in a GitHub Actions job.

- When a PR is opened, the agent reviews the code, runs tests, and posts comments.

- There is no service boundary: the agent is instantiated within the GitHub Actions runner process, and is constrained by that runner’s limits — 6-hour max job duration, fixed RAM and disk, no persistent state between runs.

Example: agentic search in a support app.

- A customer support app adds an agentic search capability to help users refine their query and find the information they need.

- The support app user chats with the agent that searches, filters and combine information from the knowledge base, ticket history,… The user can turn its search into a support ticket answer or any other relevant action.

- The agent is a function call within the app process. When the search completes (or the user navigates away), the session is gone. No agent service boundary.

In both cases, the agent runs within the host process. It starts, does its work, and stops. No independent lifecycle. No reconnection. No background continuation.

How is an Agent Server different from an Agent SDK?

The Agent Server use case

If you want to build a ChatGPT clone, an Agent SDK is a start. But it’s not enough.

You need the agent’s lifecycle to be decoupled from the client’s so that you can:

- Access from anywhere, not just a CI job or a bot on your server.

- Close your browser, come back later, and find the agent still running — or finished.

- Connect multiple people to the same agent session.

- Get real-time progress as the agent works.

You cannot just put the SDK on a server and call it done. The SDK gives you the agent loop. It does not handle what comes with running a process that other people connect to over a network:

- Authentication — who is allowed to talk to this agent, and how do you verify that?

- Network resilience — clients disconnect, requests timeout, connections drop mid-stream. The library assumes a stable in-process caller.

Agent-specific server capabilities

Authentication and network resilience need to be thought through for any client-server application. Agents require additional layers:

Transport: how the user’s browser (or app) talks to the agent server. You build an HTTP server that accepts requests and returns agent output. The question is how much real-time interaction you need. There are multiple options of growing complexity from standard HTTP request/response (the user submits a task and waits for the complete result: no progress updates while the agent works) to Websocket. See focus on the Transport layer in Part 5 for more details.

Routing: how each message reaches the right conversation. You build this by assigning a session ID to each conversation and maintaining a registry — a lookup table that maps session IDs to agent processes. When a message comes in, the server looks up the session ID and forwards the message to the right place.

Persistence: how conversations can be accessed and resumed later. You build this by “persisting” the conversation state (messages, context, artifacts). Unless the runtime is run without interruption that means saving the state and reloading it when the user reconnects. Part 5 shows how different projects solve this differently.

Lifecycle: what happens when the user closes the tab while the agent is working. When the agent runs inside the request handler, when the user disconnects, the connection closes and the agent stops. For longer tasks, you need the agent to survive disconnection. To do so, first you need to separate the agent process from the request handler. The agent runs in its own container or background process, not inside the HTTP handler.

OpenCode: the only Agent Server

OpenCode ships as a server with most layers built in.

| Layer | OpenCode provides | What it does not provide |

|---|---|---|

| Transport | HTTP API + SSE streaming. Client sends prompts via POST, receives output via SSE. | No WebSocket. SSE is one-way — the client cannot send messages while the agent is streaming without making a separate HTTP request. |

| Routing | Full session management — create, list, fork, delete conversations. Each session has an ID. | Sessions are scoped to one machine. No global registry for routing across multiple servers or sandboxes. |

| Persistence | Sessions, messages, and artifacts saved to disk as JSON files. Restart the server and conversations are still there. | Persistence is tied to the local filesystem. If the machine or sandbox is destroyed, the files are gone. No external database, no durable state across environments. |

| Lifecycle | Server continues running when client disconnects. Agent keeps processing. Reconnect with opencode attach. | No recovery from server crashes — in-flight work is lost. No job queue, no supervisor, no automatic restart. |

| Multi-client | Multiple SSE clients can watch the same session simultaneously. | Only one client can prompt at a time (busy lock). No presence awareness, no real-time sync between clients. Multiple viewers, single driver. |

| Authentication | Optional HTTP Basic Auth. | No tokens, no user identity, no multi-tenant isolation, no fine-grained permissions. |

What to keep in mind

- An Agent SDK is a library. An Agent Server is a service. The SDK runs inside your process — when it stops, the agent stops. A server runs independently — the agent survives disconnection.

- Crossing the service boundary means building four layers: transport (how the client talks to the server), routing (how messages reach the right session), persistence (how state survives restarts), lifecycle (how the agent runs without a client connected).

- OpenCode is the only agent SDK that ships as a server. It provides all four layers out of the box, scoped to a single machine. For global routing, multi-tenant access, or cloud deployment, you build the remaining pieces yourself.

Part 5 — Agent architectures by example

It’s possible to cross the service boundary without rebuilding everything OpenCode provides. Depending on the use case, you may need to implement only some of the layers.

The single biggest design decision is whether you are building a stateful or stateless agent. Statefulness can be achieved with an agent being “always on”, being hosted on a VPS for example. But that’s not scalable: you end up paying even when the agent is idle.

Alternatively relying on ephemeral environments comes with a persistence challenge: how do you persist the state when the environment is torn down?

Part 5 walks through real projects to illustrate how agents are assembled from different technical bricks, reviewing a variety of architectural choices.

Claude in the Box: the job agent

Agent Framework: Claude Agent SDK

Cloud services: Cloudflare Worker + Cloudflare Sandbox

Layers: transport + artifacts persistence

Link: github.com/craigsdennis/claude-in-the-box

Description:

- This is a job agent, not a chatbot. No conversation, no back-and-forth during execution, no session to resume.

- Use case: a job that is best performed by an agent, i.e. extract structured data from a document.

- A ~100-line project that wraps the Claude Agent SDK.

User journey: the client sends a POST request with a prompt and stays connected. The agent’s raw output streams back in real time: progress messages, tool calls, intermediate results. When the agent finishes, the Worker collects the final output files (the artifacts) and stores them in KV and returns it to the client.

Technical flow:

- The Worker receives the POST and spins up a Cloudflare Sandbox.

- The agent runs inside the sandbox using the Claude Agent SDK’s

query()function. It reads, writes files, runs bash commands — all within the container. - The agent’s stdout is streamed back through the Worker to the client as chunked HTTP. This is the live feed — a mix of everything the agent does.

- When the agent finishes, the Worker reads the output files (e.g.

fetched.md,review.md) from the sandbox filesystem. The Worker stores them in Cloudflare KV (keyed by a cookie) so the client can retrieve them after the sandbox is destroyed.

Browser → HTTP POST

→ Cloudflare Worker (~100 lines)

→ Cloudflare Sandbox

→ Claude Agent SDK query()

← streams stdout back

→ reads artifacts → stores in KV

→ destroys sandboxHighlight: Why Cloudflare requires two layers: Worker + Sandbox?

Cloudflare Workers are like application “valets”:

- They are the frontdoor for internet traffic (they handle HTTP requests) and decide what to do / which services to call. In technical terms, they route, orchestrate and connects to Cloudflare services like KV and Durable Objects.

- Additional benefit: Worlers sleep between requests and bills only for the time it runs — cheap and instant.

- Limitation: it runs in a V8 isolate — a lightweight JavaScript sandbox with no filesystem, no shell, and a 30-second CPU time limit. It cannot run the Claude Agent SDK.

The Sandbox is the opposite:

- It is a full Ubuntu container with bash, Node.js, a filesystem, and no time limit — everything the agent needs.

- But it has no public URL. It cannot receive requests from the internet or talk to Cloudflare services directly.

Neither can do the whole job alone. The Worker provides the service boundary (HTTP endpoint, streaming, artifact storage). The Sandbox provides the execution environment (bash, filesystem, long-running agent). The ~100 lines of glue between them wire up the HTTP endpoint, bridge the stream, and collect artifacts.

Server layers implementation

| Layer | Status | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Authentication | Skipped | Anyone can call the endpoint. |

| Network resilience | Skipped | If the connection drops, the work is lost. |

| Transport | Implemented (minimal) | Chunked HTTP streaming — the user watches progress in real time, but cannot send anything back. |

| Routing | Skipped | No session IDs, no conversations to switch between. Each request is independent. |

| Persistence | Partial | Final artifacts only (stored in KV). No conversation history, no ability to resume. |

| Lifecycle | Skipped | The agent dies with the request. Close the tab and the work stops. |

sandbox-agent: the adapter

Agent Framework: Agent-agnostic (supports Claude Code, Codex, OpenCode, Amp)

Cloud services: None — runs inside any sandbox (designed to be embedded)

Layers: transport + partial routing

Link: github.com/rivet-dev/sandbox-agent

Description:

- This is a transport adapter. It solves one problem (giving every coding agent a unified HTTP+SSE transport) and leaves everything else to the consumer.

- Use case: when a developer wants to deploy a variety of coding agents in sandboxes, this provides a built-in transport solution. The developer doesn’t need to understand each agent’s native protocol, and doesn’t need to change anything when switching sandbox providers.

Technical flow:

- The daemon starts inside a sandbox and listens on an HTTP port.

- The client creates a session via REST, specifying which agent to run (Claude Code, Codex, OpenCode, Amp).

- The daemon spawns the agent process and translates its native protocol into a universal event schema with sequence numbers.

- Events stream to the client over SSE.

- When the agent needs approval (e.g. to run a bash command), the daemon converts the blocking terminal prompt into an SSE event. The client replies via a REST endpoint.

- If the client disconnects, it reconnects and resumes from the last-seen sequence number.

Your App (anywhere)

| HTTP + SSE

v

+--[sandbox boundary]-------------------+

| sandbox-agent (Rust daemon) |

| claude | codex | opencode |

| [filesystem, bash, git, tools...] |

+----------------------------------------+Highlight: the Transport layer

Transport is how a client and a server exchange data over a network. There is a spectrum of transport modes, from simplest to most capable:

| Mode | What the user experiences | Interaction | Reconnection |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTTP request/response | Submit a task, wait, get the full result when done. No progress updates while the agent works. | One-shot. | N/A. |

| Chunked HTTP streaming | Submit a task, watch the agent’s output stream in real time — like a terminal in the browser. | Watch only — the user cannot send input mid-stream. | None. Connection drops = work lost. |

| Server-Sent Events (SSE) | Same real-time streaming, but the connection survives drops. The browser reconnects automatically and resumes from the last event. | Watch + interact via separate requests (e.g. approve a command via a button click). | Built-in (automatic). |

| WebSocket | Full interaction while the agent works — approve commands, provide context, cancel tasks. Multiple users can watch the same session. | Bidirectional, real-time. | Application must implement. |

Claude-in-the-Box uses chunked HTTP streaming. sandbox-agent outputs SSE. Ramp Inspect uses WebSocket. Each step up adds capability and complexity.

Now, the agents that sandbox-agent supports speak different native protocols — none of which are network transports:

- JSONL on stdout — Claude Code and Amp run as child processes, spawned per message. They write one JSON object per line to stdout.

- JSON-RPC over stdio — Codex runs a persistent server process (

codex app-server) that communicates via structured JSON-RPC requests and responses over stdin/stdout. Still a local process — not network-accessible. - HTTP server — OpenCode already runs its own HTTP+SSE server (see Part 4). It is network-accessible without translation. For OpenCode, sandbox-agent is not necessary.

Server layers implementation

| Layer | Status | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Authentication | Skipped | Runs inside a sandbox — assumes the sandbox boundary provides isolation. |

| Network resilience | Partial | SSE sequence numbers allow clients to reconnect and resume from last-seen event. |

| Transport | Implemented | HTTP + SSE — structured event stream with sequence numbers for reconnection. REST endpoints for approvals/cancellation. |

| Routing | Partial | In-memory session management — multiple sessions per daemon, but no persistent session registry. |

| Persistence | None | If the daemon crashes or the sandbox is destroyed, there is no way to recover or reconnect to a conversation. |

| Lifecycle | Minimal | Agent process managed by the daemon, but no background continuation beyond the sandbox’s lifetime. |

Ramp Inspect — the full production stack

Agent Framework: OpenCode

Cloud services: Modal Sandbox VMs + Cloudflare Durable Objects + Cloudflare Workers

Layers: transport + routing + persistence + lifecycle + authentication + network resilience (all layers)

Link: builders.ramp.com/post/why-we-built-our-background-agent

Description: Ramp’s internal background coding agent that creates pull requests from task descriptions. Reached ~30% of all merged PRs within months.

User journey: an engineer describes a task in Slack, the web UI, or a Chrome extension. The agent works in the background — the engineer can close the tab, switch clients, come back later from a different device. When done, the agent posts a PR or a Slack notification. Multiple engineers can watch the same session simultaneously.

Technical flow:

- Each task gets a session — one session = one Durable Object + one Modal VM + one conversation. The session ID is the permanent address for the task.

- The client connects via WebSocket to a Cloudflare Worker, which routes the connection to the session’s Durable Object.

- The DO is the hub: it holds WebSocket connections from all clients watching this session, stores conversation history in embedded SQLite, and forwards messages to the Modal VM. When the agent produces output, the DO broadcasts it to every connected client.

- The VM runs OpenCode with a full dev environment: git, npm, pytest, Postgres, Chromium, Sentry integration.

- The agent works independently of any client connection. If all clients disconnect, the VM keeps running.

- On completion, the agent posts results via Slack notification or GitHub PR.

- Modal VMs have a 24-hour maximum TTL. Before the VM is terminated, its state is captured through Modal’s snapshot API — a full point-in-time capture of the filesystem (code, dependencies, build artifacts, environment). The snapshot can be restored into a fresh VM days later.

Clients (Slack, Web UI, Chrome Extension, VS Code)

→ Cloudflare Workers

→ Durable Object (per-session: SQLite, WebSocket Hub, Event Stream)

→ Modal Sandbox VM (OpenCode agent, full dev environment)Highlight: Durable Objects as the coordination layer

In Part 4, we saw that OpenCode is a single-server agent — it has session management, persistence, and transport, but all scoped to one machine. To make it globally accessible, you need global routing, persistent state that survives restarts, and WebSocket management across clients. This is the gap Ramp filled with Durable Objects.

A Durable Object is a stateful micro-server with a globally unique ID (while Workers are stateless). Any request from anywhere in the world can reach a specific DO by its ID — Cloudflare routes it automatically. Each DO has its own embedded SQLite database (up to 10 GB), and it can hold WebSocket connections. It runs single-threaded, which matches the agent pattern: one session = one sequential execution context.

What makes DOs useful for agents specifically:

- Global routing without a registry. The DO ID is the session address. No load balancer, no session-affinity configuration, no lookup table. A client in Tokyo and a client in New York both reach the same DO by passing the same ID.

- State that survives hibernation. When no clients are active, the DO hibernates — it is evicted from memory but the WebSocket connections are kept alive at Cloudflare’s edge, and the SQLite data persists. Billing stops. When a client sends a message, the DO wakes up, the message is delivered, and processing continues. The client does not know the DO was hibernating.

- Re-attach for free. If a client actually disconnects (browser closed, network drop), a new connection to the same DO ID restores the session. The conversation history is in SQLite. Cloudflare’s Agents SDK (which builds on DOs) goes further: it automatically syncs state on reconnection and can resume streaming from where it left off.

Why a Modal VM is required on top of the DO:

A DO is a lightweight JavaScript runtime — it cannot run bash, access a filesystem, or execute agent tools. It is the coordination layer (routing, state, WebSocket), not the execution layer. Code execution happens in a separate VM or container. This is why Ramp pairs DOs with Modal VMs: the DO routes and remembers, the VM computes.

Server layers implementation

| Layer | Status | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Authentication | Internal only | Restricted to Ramp employees — no public access. |

| Network resilience | Implemented | WebSocket with DO hibernation — connections survive idle periods, clients reconnect seamlessly. |

| Transport | Implemented | WebSocket — bidirectional, real-time, multiple clients connect to the same session simultaneously. |

| Routing | Implemented | Cloudflare Durable Objects — per-session, globally routed, guaranteed affinity by session ID. |

| Persistence | Implemented (two layers) | DO SQLite for conversation state + Modal snapshots for full VM state (code, deps, environment). |

| Lifecycle | Implemented (full) | Agent survives client disconnection — background continuation is the core design principle. |

Cloudflare Moltworker — the platform provides the layers

Agent engine: Pi SDK (LLM abstraction + core agent loop)

Agent product: OpenClaw (personal AI assistant built on Pi SDK — multi-channel gateway, session management, skills platform)

Cloud services: Cloudflare Worker + Durable Objects + Sandbox + R2 + AI Gateway

Layers: ALL (transport, routing, persistence, lifecycle, authentication, network resilience)

Link: github.com/cloudflare/moltworker — blog: blog.cloudflare.com/moltworker-self-hosted-ai-agent

Description:

- OpenClaw (previously Moltbot, ex-Clawbot, ex-Clawdis) is all the rage since January: a personal assistant that you can work with from your messaging app. There are different options for hosting, the first being you own computer or a VPS. Cloudflare Moltworker project provides an option to deploy it on Cloudflare ecosystem.

- The stack has three layers: Pi SDK provides the agent engine (LLM calls, tool execution, agent loop). OpenClaw builds a complete personal assistant on top of Pi — multi-channel inbox (WhatsApp, Telegram, Slack, Discord), its own session management, a skills platform, and companion apps. Moltworker is the deployment layer — it packages OpenClaw into a Cloudflare container, handles authentication (Cloudflare Access), persists state to R2, and proxies requests from the internet to the agent.

User journey: the user accesses their agent via a browser, protected by Cloudflare Access (Zero Trust). They chat with the agent, which can browse the web, execute code, and remember context across sessions. They can close the browser and come back — conversations persist. The agent can also run autonomously on a cron schedule with no client connected at all.

Technical flow:

- The browser connects through Cloudflare Access, which enforces identity-based authentication before any request reaches the application.

- The Worker receives the request and routes it to the appropriate Durable Object instance.

- The Durable Object establishes a WebSocket connection with the client and manages the container lifecycle — same pattern as Ramp (DO → compute), but here the compute is a Cloudflare Container instead of a Modal VM.

- The container (a full Linux VM) runs the OpenClaw agent. It has an R2 bucket mounted at

/data/moltbotvia s3fs for persistent storage. - When the user goes idle, the container sleeps (configurable via

sleepAfter). The Durable Object hibernates without dropping the WebSocket. - On the next message, the DO wakes, the container restarts, and the R2 mount provides continuity — session memory and artifacts survive the restart.

Internet → Cloudflare Access (Zero Trust)

→ Worker (V8 isolate, API router)

→ Durable Object (routing, state, WebSocket)

→ Container (Linux VM, managed via Sandbox)

→ /data/moltbot → R2 Bucket (via s3fs)

→ OpenClaw (Pi SDK agent)Highlight: how persistence works with ephemeral compute

Both Ramp and Moltworker face the same problem: the agent runs in an ephemeral machine (Modal VM or Cloudflare Container) that will eventually be destroyed. How do you keep state across restarts?

The 2 projects made different design decisions:

- With Modal, and its snapshot feature, the full state of the VM is saved and restored. There is no need to think ahead what information needs to be saved and restored.

- Cloudflare Containers don’t have the same feature. So the approach with Moltworker is to provide an additional persistance layer: the agent has a sort of virtual drive that rely on a Coudflare R2 bucket (a storage product similar to AWS S3). Meaning that part of the filesystem (located

/data/moltbot) it is automatically saved. But not all of it.

| Ramp (Modal) | Moltworker (Cloudflare) | |

|---|---|---|

| What dies | VM is terminated after 24-hour TTL | Container filesystem is wiped on sleep |

| Conversation state | Stored in Durable Object (SQLite) — survives VM restarts | Stored in Durable Object (SQLite) — survives container restarts |

| Code, deps, environment | Modal snapshot API — full point-in-time capture of the VM filesystem. Taken before termination, restored into a fresh VM later. | R2 bucket mounted at /data/moltbot via s3fs — everything written there survives. No snapshot, just continuous persistence. |

| What survives | Everything (full VM state frozen and restored) | Only what’s explicitly written to /data/moltbot |

| What’s lost | Nothing (if snapshotted before termination) | Anything on the container filesystem outside the R2 mount |

| Trade-off | Full fidelity but requires snapshot orchestration | Simpler but selective — you must design for it |

Server layers implementation

| Layer | Status | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Authentication | Implemented | Cloudflare Access (Zero Trust) — identity-based access control before any request reaches the application. |

| Network resilience | Implemented | DO hibernation keeps WebSocket alive during idle periods. Container wakes on next message. |

| Transport | Implemented | WebSocket (via Durable Objects) + HTTP API for the entrypoint Worker. |

| Routing | Implemented | Durable Object instance IDs — globally routable, all requests for same ID reach the same location. |

| Persistence | Implemented | Multi-layer: DO SQLite for conversation, R2 bucket mounted via s3fs for artifacts and session memory. |

| Lifecycle | Implemented | Agent survives client disconnection. DO hibernates. Containers sleep/wake. Cron enables autonomous runs. |

What to keep in mind

- Not every use case needs all the layers. Claude in the Box ships a useful product with just HTTP streaming and KV storage.

- Transport is a spectrum — pick the simplest that fits. Chunked HTTP for job agents (Claude in the Box), SSE for streaming with reconnection (sandbox-agent), WebSocket for bidirectional interaction and multiplayer (Ramp, Moltworker). Each step up adds capability and complexity.

- Background continuation requires decoupling the agent from the HTTP handler. The agent runs in its own process or container, not inside the request.

- Statefulness is the main design choice and the principal source of complexity: resumable conversations require persistent routing (so the client finds the right session), storage and coordination layers that outlive the agent execution environment.

Going further

-

LangGraph — Thinking in LangGraph

The mental model behind app-driven orchestration: explicit graphs, state machines, and developer-defined control flow. Includes the email-triage workflow example.

https://docs.langchain.com/oss/python/langgraph/thinking-in-langgraph -

Unix Was a Love Letter to Agents — Vivek Haldar

Argues that the Unix philosophy — small tools, text interfaces, composition — aligns perfectly with how LLMs work. “An LLM is exactly the user Unix was designed for.”

https://vivekhaldar.com/articles/unix-love-letter-to-agents/ -

Vercel — How to build agents with filesystems and bash

Practical guide to the filesystem-and-bash pattern. “Maybe the best architecture is almost no architecture at all. Just filesystems and bash.”

https://vercel.com/blog/how-to-build-agents-with-filesystems-and-bash -

From “Everything is a File” to “Files Are All You Need” (arXiv 2025)

Academic paper arguing that Unix’s 1970s design principles apply directly to autonomous AI systems. Cites Jerry Liu: “Agents need only ~5-10 tools: CLI over filesystem, code interpreter, web fetch.”

https://arxiv.org/html/2601.11672 -

Turso — AgentFS: The Missing Abstraction

Argues for treating agent state like a filesystem but implementing it as a database. “Traditional approaches fragment state across multiple tools—databases, logging systems, file storage, and version control.”

https://turso.tech/blog/agentfs -

How Claude Code is built — Pragmatic Engineer

Deep dive into Claude Code’s architecture. “Claude Code embraces radical simplicity. The team deliberately minimizes business logic, allowing the underlying model to perform most work.”

https://newsletter.pragmaticengineer.com/p/how-claude-code-is-built -

What I learned building an opinionated and minimal coding agent — Mario Zechner

The author of Pi SDK on building a coding agent with under 1,000 tokens of instructions and no elaborate tool set. “If I don’t need it, it won’t be built.”

https://mariozechner.at/posts/2025-11-30-pi-coding-agent/ -

Agent Design Is Still Hard — Armin Ronacher

Building production agents requires custom abstractions over SDK primitives. “The differences between models are significant enough that you will need to build your own agent abstraction.” Covers cache management, failure isolation, and shared filesystem state.

https://lucumr.pocoo.org/2025/11/21/agents-are-hard/ -

Minions: Stripe’s one-shot, end-to-end coding agents — Alistair Gray

Stripe’s homegrown coding agents that operate fully unattended — from task to merged PR — producing over 1,000 merged PRs per week. Orchestrates across internal MCP servers, CI systems, and developer infrastructure.

https://stripe.dev/blog/minions-stripes-one-shot-end-to-end-coding-agents -

The two patterns by which agents connect sandboxes — Harrison Chase

Agent IN sandbox (runs inside, you connect over the network) vs sandbox as tool (agent runs locally, calls sandbox via API). Each has different trade-offs for security, iteration speed, and coupling.

https://x.com/hwchase17/status/2021261552222158955